Sarah Stein’s essay “Multimedia as Persuasive Agent: Using Visual Metaphors to Establish the Rhetorical Agenda in a Communication Department Video” (2000) described an irony that sticks with us sixteen years on: for all we do to teach the history and practice of video, of persuasion through a mix of media, and of visual metaphor, humanities departments still struggle to create videos that tell good stories about their own research.

That irony is only surface-deep, though. Our departments have to leap the same bars all academic programs do when it comes to video production, namely securing (1) access to production tools—cameras, light kits, editing software, and methods of distribution; (2) skilled video makers; and (3) content that lends itself to visual storytelling.

Advances in low-cost tools, digital distribution, online training, and wider fluency in visual rhetoric have mitigated those first two issues. But the third—content—remains the big hurdle.

It’s easy to see why.

Visual storytelling requires visual material, but much research is largely abstract. At my institution, MIT, its mechanical engineers get to illustrate machine vision research with videos of robot cheetahs. Our physicists make gravitational waves understandable through three-dimensional visualizations. But humanities and social science programs, at MIT and elsewhere, produce a lot of research with no physical, that is, filmable, analog. Consider Michael J. Lee’s Creating Conservatism: Postwar Words that Made an American Movement. How would a department make a video about words?[1] It can, but not with the ease my MIT science colleagues can make a video about those robots or CRISPR or colliding black holes (McGovern 2014).

Nevertheless, prospective students, university media relations staff, fellow scholars, and a growing number of administrators expect video to play a role in telling stories about research, no matter how easily ideas translate to visuals. Video should communicate research as readily as it does public events, administrators argue, and it should be a natural part of a department’s outreach strategy, no different than, say, articles in a departmental magazine. Video should be a gateway through which audiences can approach research.

As administrators know, though, the resources and skill-sets needed to translate abstract research into a story using video is often not available at the department level. They often exist higher up at an institution, intended to serve the needs of university-wide offices such as admissions and development, or lower down, within courses, where faculty teach production but might not consider it appropriate to require students to produce material on behalf of a department’s communications efforts. Courses are also where production quality is not the primary concern, since students are learners, allowed to experiment and fail in the service of learning, and, as Stein’s study points out, do not work on a schedule aligned with the department’s.

The expectation that a program should produce video then leads some departments to hire outside production companies. The quality of such videos can indeed be superb. With creative ideas behind them, well-expressed, these videos can even enjoy some spreadability (Jenkins 2009). But their production costs are in the thousands of dollars, precluding not just routine and timely production of videos but also the option to tell a story about an individual piece of research, such as a whitepaper, a student project, or a new faculty book. Instead, budgeting at this level is reserved for an evergreen, non-narrative “About Us”-style video, covering the program as a whole.

But not having a way to regularly produce high-quality, inexpensive video about research comes with its own costs. My department’s field plays a direct role in civic life, for example. It teaches students how to create and unpack suasive messages. It informs our understanding of how technology shapes or distorts perception. It provides insight into how changes in media tools, practices, and distribution can democratize or close off access to certain makers and audiences. And through its studies of ethics, it serves as an intellectual bridge between economics, public policy, new media studies, and even the fine arts. Proficiently translating its research to video is like adding a lane; failing to do so is like leaving one closed.

To review the challenge then: departments need quality videos about their research, ideally with a structure. Those videos must be made with some regularity, not as a one-off. Yet they cannot be produced by students nor with the high cost of outside production companies.

What options are left? This paper provides some answers and cautions.

Its intent is to be a guide to administrators, particularly those in small- to medium-sized programs without a major media production component, as they consider the use of video in communicating their program’s research. It uses surveys and interviews with department heads, case studies from my own productions, and, based on them, a set of recommendations, all to answer two questions: what does a department need (and not need) to produce a video that tells a story about research, and how does an administrator determine whether the benefits outweigh the costs of producing such videos on a regular basis?

Project Background

It’s tough to overstate the amount of change in video production since Stein authored her piece in 2000. Where Stein described the affordances of VHS tape, today departments debate the pros and cons of Snapchat. Where she touted her video’s twelve-minute runtime, today we aim to keep them under three.[2]

This project, conceived in 2014 somewhat differently as “documenting humanities research through narrative video,” was done in three phases. First, an undergraduate researcher (Hannah Wood, ’15) and I identified and reviewed existing humanities and social science departmental videos. We found that what Stein described in 2000 remains largely true today: videos tend to be about departments themselves, not about specific research, and they tend to be produced either inexpensively by using students with faculty oversight or expensively by using outside production companies. We learned the latter via our second phase: surveys of, and follow-up phone conversations with, communication department leaders (Whitacre and Wood, 2014a; Whitacre and Wood, 2014b). Of the thirty-four department leaders we surveyed and the ten we followed up with, none described having yet found a middle path between nearly-free, student-produced video and expensive, professionally-produced video.

This is consistent with my knowledge of other humanities and social science programs in schools in the Boston area, whose communications professionals I regularly work with. While the area’s schools have made many video production hires, those positions are:

- in units with, and expected to raise, large amounts of external funding/sponsored research, such as business schools or consortia;

- in central offices that provide fee-for-service media production;

- in high-profile athletics departments;

- or in distance learning enterprises such as EdX or the Harvard Extension School.

I also searched LinkedIn for local higher education professionals with the term video in their profiles, and the results are consistent. Of the 2,050 LinkedIn results, other than my own, I failed to find a single local staffer based in an academic department[3] who produces video as part of their job. Yet our survey shows this is a skill departments want.

Other findings from the follow-up conversations are helpful for administrators to consider for context. Programs rarely spent more than $100 on a video, not including equipment, software, or time. (See Budgeting below for a breakdown on what it would cost to create a video-making infrastructure from scratch.) Only one respondent described their video as having a narrative; the rest were either purely informative/promotional or recordings of public events. Of administrators that discussed their intended audiences, all of them said one of their audiences was prospective students.

Lastly, respondents touched upon two issues they originally overlooked.

First is what they called videos’ rapid “obsolescence”—their short shelf-life. There are the unplanned-for versions of obsolescence, such as when my department produced videos for a research group whose principal investigator then left for another school, thereby changing the project’s institutional affiliation, or there are the changes in a department’s goals, where a great video suddenly has to take a back seat to another one with a new focus. Then there is the nature of scholarship itself. It advances. Where scholars enjoy the steady build-up of knowledge, a producer watches a video’s erosion of relevance. A breakthrough can make a video outdated overnight.

The second oft-overlooked issue is a legal one. A lawsuit against Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology by the National Association of the Deaf argues that videos used in online education must meet captioning requirements spelled out in the Americans with Disabilities Act (Gayla 2015). Until the suit is resolved, administrators should keep a berth space between video that is used to tell stories about research and video that is used to teach.[4]

After completing this preliminary research and surveys, my undergraduate researcher and I set out to produce three videos to serve as case studies. We purposefully did them “naively,” with no experience producing videos on research, to best illustrate what it would be like for a department to start from zero with regard to in-house skills. However, because our program offers two documentary production courses, it already owned cameras and light kits, and MIT provides an array of software free to faculty, staff, and students, including editing software such as Final Cut and Adobe Premiere. We took advantage of both. For the budget, this paper assumes other departments also have existing access to lightkits and software but does outline a range of cameras.

I hired the undergraduate researcher through a program run by MIT that matches undergraduates with research projects. Departments submit a position description to the program’s office, with the core requirement being the position must provide the student with research experience, not general work experience. Undergraduates apply, the hired student(s) propose a work-plan aligned with the research opportunity’s needs. The department reviews and accepts the work-plan. In return, the student(s) receive either payment or course credit. In this case, we advertised for a position that would earn course credit. Our undergraduate researcher thus came at no cost. The cost of my own time was already built into my salary, but naturally this came with an opportunity cost: adding video production to my work meant not doing something else of value to the department. In the Budgeting section below I have included an estimate of the dollar value of a staffer’s time; administrators can use that as a measure of whether that amount is best spent on video or something else.

For the subjects of the videos, we chose what we thought would be representative of the kinds of videos a department using our criteria (about research, story-based, low cost, modest skills, short timelines) would make. I have ordered them from least successful to most successful.

The lessons at the end of each case study—and the recommendations I make at the end of the paper—gloss over general video best practices, the kinds of things one would learn in regular production training. Instead they focus on the challenges relevant to videos about research produced by academic departments in the kinds of spaces they commonly have access to.

Case studies

Case Study 1: “Data Storytelling Studio” Student Presentations

The most common filming request in my department is to record student presentations.

Typically, videos of presentations on their own would not meet this project’s requirements. They do not consist of stories, and they are not about discrete pieces of research. However, their advantage is the large amount of raw material they provide that can be paired later with more targeted material, together creating a research video. They are perhaps the largest and lowest-effort source of content—and of huge variety: video of students, of instructors, of physical spaces, question-and-answer sessions, speaker audio, slides, text, code, models—that can be woven into a narrative.

For our first case study, therefore, we set out to record the visuals-heavy set of final presentations from our department’s Data Storytelling Studio.[5] The approach was to record the teams presenting their work (which consisted of slides and physical prototypes), identify the best presentations (in terms of academic quality and value for video), acquire their slides to use as b-roll, and, importantly, interview a small number of students about their work and the instructor about the value of the course. In fact, that last purpose—interviewing the instructor—was to be the heart of the research component of the video. He would provide an overview of “storytelling with data” and walk the viewer through the young field’s impact; the presentations, slides, and prototypes would serve as illustrations of key points made by the instructor. It would effectively serve as an expansion on Stein’s approach in 2000, which relied only on graphics to increase viewer engagement. (297)

That was the plan at least. The recording of the presentations went poorly enough that we abandoned the rest. Here’s why.

Setup. We believed that recording presentations, particularly of teams and which use projected slides, lends itself to a camera setup at the back of the room. We positioned our camera in a back corner of a classroom roughly forty feet from front to back with a large pull-down screen in the front, in order to have presenters and slides in the same shot when needed. (See Figure 1.) Of the two rear corners, we chose the one that left a large bank of side windows out of the frame, allowing for natural light to illuminate the speakers. We also adjusted the window shades to get the desired light.

For recording audio, we employed a camera-mounted shotgun mic. We had planned to use wireless lavalier mics but were unable to, for reasons described below.

We coordinated with the instructor beforehand, so that he could make an announcement to the class that we will be recording, giving students the chance to opt out.

Execution. It was immediately clear we had planned poorly. We intended for the shotgun mic to be a supplement to a lavalier mic, both for redundancy in case the lav mic failed and to allow us to capture questions from the class and instructor at the end of each presentation. However, at the last minute, the camera we intended to use became unavailable (a student shooting a final assignment for another class was given priority), and the camera that was available didn’t accept a wireless lav mic input, which we only discovered on-site.

Audio, then, was produced solely with the shotgun mic. Such mics are excellent at capturing audio at our forty-foot distance, and by design they capture much less of anything out of their direct line. But while they can cut through ambient noise generally, they struggle if that noise reverberates.[6] This classroom’s design was one common to university buildings designed in the early to mid 20th century, with high ceilings, concrete walls, and tile floors. Voices echoed. Chair legs scraped along the floor. The shotgun mic could have been a satisfactory option in a lower-ceilinged, carpeted, drywalled room, but in either venue, capturing speakers’ voices with lavalier mics would have been superior.

In post-production, the audio reached a minimally acceptable quality, but the higher audio quality of the planned interview with the instructor would have created a distractingly stark difference.

Visuals also suffered, due to the specific equipment we used and how it worked poorly with a group presentation format. Group presentations require panning and reframing as speakers pace and take turns. The tripod we used, however, had an older ball-head mount that made it difficult to move the camera smoothly. In reviewing the footage, it was clear we would not be able to use the video we we took during pans or tilts. Yet such movements were necessary to capture each speaker in a medium close-up, tracking them as they gesture or shift from one foot to the other.

The failure to capture good audio and video from the presentations, leaving us with quality far different than what we would have captured from instructor interviews, was enough for us to decide to shelve this production. But even if we hadn’t, a head-smack complication awaited us. By definition, final presentations are at the end of the term: it thus wasn’t an option to interview the instructor, because he had left campus for the summer.

- Avoid using student presentations as the starting point of content for your video. Begin instead with the instructor and his or her research, producing such video earlier in the semester, leaving the filming of presentation footage for the end.

- If the presentations are in a large classroom and lav’ing each speaker would be too complicated, use a standalone omnidirectional recorder at the front of the room and sync its recorded audio to video afterward.

- Related, a shotgun mic mounted on a camera at the rear of a room can be a big liability given the way inexperienced presenters sometimes position themselves, turning their backs to the audience in order to refer to their projected slides. This can cause the recorded speech to alternate between clear and inaudible.

- Instead, position the camera at the side of the room, slightly more than halfway to the front. By doing so, you also have more opportunities to film faces during Q&A, allowing the shotgun mic to capture better audio from them.

- Work with the presenters. Mention to them ahead of time that they will be filmed, not only for purposes of consent but for them to be aware, if they are speaking as a group, of not standing between the camera and another speaker. You can also encourage them to stand on a mark set on the floor on the opposite side of the projection screen from the camera, allowing the camera to see their face whether they are turned toward the audience or toward the screen.

- Request presenters’ slides and other material. Even if you were positioned at the rear of the room, slides are often illegible on video. There will also be times speakers refer to a specific detail in their slide or play embedded audio or video. Having slides and media files allow you to intercut them.

- When all else fails in during the shoot, film b-roll. Grab video of audience reactions, close-ups of hands taking notes, etc. (See Figure 2.)

Case Study 2: Animated Illustrations

Live-action visuals aren’t the only option when telling stories about research. Text, images, data visualizations, and animation are great too, especially in combination. They can tell full stories in the tight times video demands and, done right, are a way to turn the audience’s focus toward sound, such as when the research a speaker describes is about music.

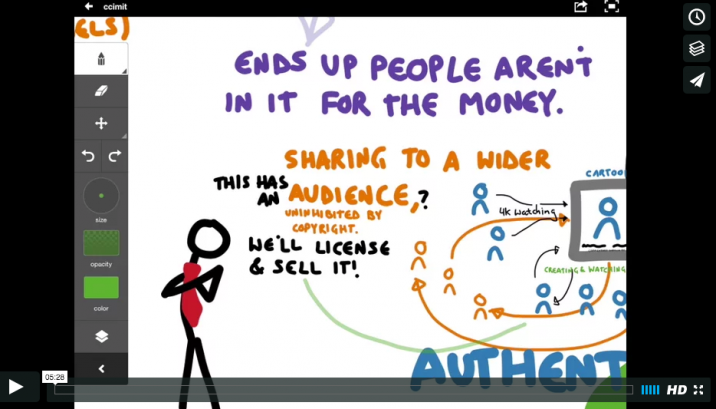

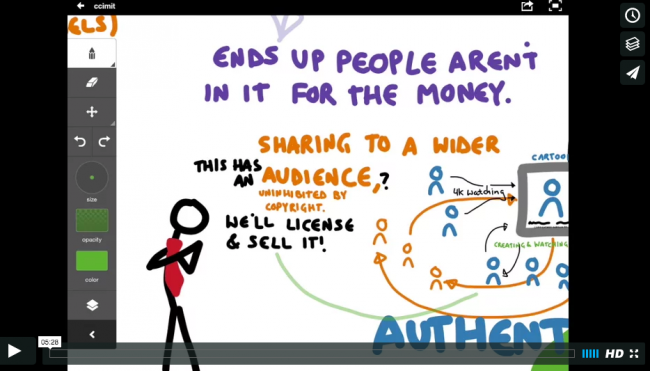

For our second video, my undergraduate researcher and I decided to interview Professor Ian Condry, who brings an anthropologist’s take on Japanese hip-hop. From prior work together, we already knew his stories were entertaining, as he had done fieldwork within the Japanese hip-hop club scene. His work also seemed to lend itself to mixing mediums within our production. For content, then, we recorded a conversation with him about his work, used songs and music videos that could act as either a music bed or be cut to as Condry referred to them, and—central to this case study—arranged for a colleague to act as illustrator and provide animated visuals with her live-sketch note-taking method.

Setup. Because the interview required capturing audio only, the setup was straightforward. We conducted it in Condry’s office at a small table. We used two audio options, both placed on the table. One was a laptop, running Audacity (a free and open-source multi-track audio editor and recorder), with a Blue Snowball microphone attached. The other was a camera paired with a lavalier mic. Even though we would not be capturing video, the camera was needed to connect the mic to physical storage, in this case an SD card. We used iMovie, Macs’ native video editing application, to capture the output from the camera.

The animated visuals were produced later by the illustrator, who recorded her screen as she sketched her interpretation of the interview audio, in real time, on an iPad running Adobe Ideas.

Professor Condry recommended music clips. He provided some himself, and we downloaded others from YouTube with keepvid.com, following guidelines on fair use.

We submitted the unedited conversation audio file online to 3Play Media to transcribe and timestamp it and used the transcription to identify segments that could be turned into a story.

It is worth noting that almost none of the tools described—SD cards (1999), iMovie (1999), Audacity (1999), high-quality USB microphones (2005), YouTube (2005)—were widely available when Stein filmed her video.

Execution. For a second time, redundant audio recording proved essential, this time due to human error: the Audacity + Snowball input worked as intended, but for the iMovie version, we pressed the record button on the camera rather than clicking the record icon in iMovie. We believed we were recording audio via the lav mic when we were not.

The creativity of the illustrations exceeded our expectations. However, we should have planned for two issues that, in retrospect, should have been obvious. The first was that the illustrator was doing us a favor—volunteering instead of doing it for compensation—which gave us no leverage when she found herself with other pressing deadlines and could not keep to the agreed-upon schedule. This overlapped with the second issue. The workflow was supposed to be:

- The undergraduate and I would record the interview and pass the illustrator the full unedited audio so she could get a sense of the material.

- She would identify portions of the audio that lent themselves best to illustration.

- With the 3Play Media transcription as a reference, the undergraduate and I would use the illustrator-suggested portions and other clips that we believed helped tell the full story to create the final audio, which we would pass back to the illustrator for her to illustrate.

Instead, as the illustrator fell behind on step two, we continued to check in with her over the course of several weeks. In our check-ins, we failed to reiterate the scope of step two, of “identifying portions of the audio”. Expressing some apology for the delay, she then sent us, unexpectedly, an illustration of the entire recording. That explained the delay. We had intended to edit down the recording based on a first round of thoughts from the illustrator. Instead, she had illustrated the entire 30-minute conversation when the final audio would only be 5 minutes.

We found ourselves needing to edit the recording around the illustration she had provided. We had to manipulate the illustration, including cropping and awkward re-pacing, to best fit the illustration with the final audio. As one can see, the illustration is visually engaging but disconnected from the narrative of the audio content.

The audio content itself was excellent, because the interview subject is a great talker and, importantly, we had enough time to let the conversation flow naturally, surfacing great anecdotes.

Lessons. Illustrations/animation/visualizations are a good option for producing compelling research video, whether on their own or as a complement to live action video:

- Talent surrounds you. There is enormous value in partnering with an artist already in your community. When identifying contributors, don’t limit yourself to the obvious ones—like asking a photography instructor to take photos. Instead, get to know people’s non-professional creative interests, especially those of staff or junior researchers. They often appreciate the opportunity to bring outside talents into their professional work.

- However, compensate them in some way, as a way both to acknowledge the value of their work and have a conversation about deliverables. Schools often have policies against direct compensation for work outside an employee’s job, but there are workarounds, from gift cards, to a drink or meal, to a don’t-include-it-in-your-timesheet day off. Don’t forget to give credit, too, whether in the video itself or anywhere it is posted.

- Expectations, deliverables, and timelines need to be clear when working with a contributor.

- Audio recording always needs redundancy. Journalists use two devices when recording interviews, and so should you.

- Review fair use guidelines. If you haven’t delved into fair use for your department’s productions before, you will find the guidelines can be both broader and more restrictive than intuition might tell you.

- If you know exactly what you want from an interview subject, go straight at it. If you’re not sure though, as we weren’t in this case, budget at least five times as much time as the final video length to allow a natural, unguided conversation to happen. That conversation will eventually drill down into not just the core of the research but personal stories that illustrate it.

Case Study 3: Using Archival Video

Another professor in my department, Heather Hendershot, is a scholar of conservative media, with a focus on the push and pull between so-called mainstream and extremist conservatism as played out in television programming. This third case study was a feature on her new book, on the role played by Firing Line, the William F. Buckley current affairs program, in the rise of conservatism after the 1960’s.

The publication of a book is the most common reason MIT’s news office will assign one of its reporters to cover a humanities story. “Our mandate is to promote peer-reviewed research,” the News Office frequently reminds MIT communications staffers, so the office’s resources (reporters/media relations, websites, social media, mass emails) prioritize articles published in major peer-reviewed journals and in new books. Many of these publications are then featured on MIT’s homepage, which has an average monthly audience of 1 million to 1.2 million. One way to make it likely the News Office brings its resources to bear on the book’s promotion is to produce a video that coincides with the publication’s release—in other words, to save them time.

While there was well over a year between Hendershot’s completing her manuscript and the publication date, we decided to work with a timeline of two months, which is more typical. It also allowed us to define a time-bounded goal for the key component of this case study: identifying, acquiring, and incorporating archival video.

Setup. Our camera setup was straightforward. We positioned it on a tripod in the a corner of Hendershot’s office, using natural light for illumination. (See Figures 6a and 6b.) We used standard interview positions. Hendershot was seated and answered open-ended questions from me as I stood just to the camera’s side (though the camera’s height should have been more eye-level). We again used a shotgun mic due to the unavailability of the camera with a lav mic input.

Importantly, we consulted with Professor Hendershot beforehand to identify sources of archival material. She pointed us to the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, which houses the Firing Line archive and was the key resource in her own research.

As is increasingly common for television video archives, the archivists at the Hoover Institution had converted recordings of the original broadcasts into web-friendly formats and released them to the public in batches. Somewhat less commonly, it has posted only a subset of those episodes online, and only as clips, opting instead to sell full episodes on DVD or stream them to Amazon Prime subscribers.

People wishing to use material from episodes must also pay a permissions fee—officially $500 for a clip no longer than ten minutes long but, unofficially, negotiable based on its intended use.

Note that this means that unless you are near this particular archive, there are many episodes you will not be able to preview before purchasing a copy. To the archive’s credit, their mix strikes a good balance between accessibility and funding its own overhead, though their approach may dissuade researchers unable to pay the archive’s fees.

Execution. The professor and I conferred over email about what topics would be most interesting to cover. That allowed me to check the archives for illustrative clips before putting together a set of interview questions.

Hendershot was an adept interview subject, understanding that the editing process meant she could start, stop, or revise her answers. The video production went smoothly and covered the ground needed. Audio was better than average but still not professional-quality; the HVAC system of the building we recorded in generates a low hum that residents usually do not notice but which can be prominent in recordings. We mitigated this by adjusting the thermostat in her office and recording thirty seconds of ambient sound for automated removal in post-production.

Securing permissions and copies of Firing Line videos took roughly a month and could have taken less had deadlines been tighter.

We edited the video in Final Cut, exported the resulting audio for touch-up in Audacity, and replaced the old audio with the new for the final video.

- Archival video is often worth the cost, if any, because by definition the production is already complete. There is so much less time involved in simply identifying in and out points in someone else’s high-quality video than in shooting fresh minutes of video yourself. This makes research videos with archival material attractive.

- Even indoors, unless you are in a studio, it is almost impossible to record without some HVAC noise. So follow the best practice of recording half a minute of the room’s ambient sound. That sound can be dialed down in post-production.

- Iterate on the focus of the video and the archival material available. You may find archival video that is so compelling that it’s worth emphasizing a different part of the research. Or in your conversations with a researcher, you may find you need to revisit items in archives that you had original discounted.

- Again, review fair use guidelines. Just because an archive charges for permission, you may not actually need it.

- Account for the archives you have access to. That includes collections within your own institution and collections you may have access to via your libraries or school consortia.

- Consider shared department subscriptions to things like Amazon Prime, YouTube Red, etc., where you can use other tools to capture video within fair use limits.

- Get to know your library liaison, who can direct you to archival sources.

Recommendations for Administrators

All of this boils down to some concrete recommendations for administrators, some of which mirror those in Stein’s essay and others that only became applicable with today’s technology. Two small-bore recommendations that show how far we have come since her 2000 paper include not attempting to squeeze the full diversity of a department in a single three-minute video and not needing to factor in the cost of distribution, as she did with VHS tapes (295).

Have a bias toward productions with ready-made content. If you are fortunate to have a few research stories to choose from, have a bias toward the one that has the most ready-made content. Despite the execution failure of the first case study, we would have been able to take advantage of the content made by others before the production. Because the students had created slides and prototypes, we would have been able to cut to original files of slides and video close-ups or photos of prototypes as they presenters mentioned them. That was the built-in benefit of the third case study as well: archival footage is often easily available and, for less experienced producers, is often a source of video of higher quality than their own.

Staffing

Unless your department places a high priority on video production, there is no compelling reason to hire a staff member whose job is dedicated to producing any kind of video, let alone ones specifically about research.

Instead, one or two staff positions should have a percentage of their responsibilities assigned to research video production. Ideally this would be a position similar to many departments’ “communications manager” or “communications specialist”, a person familiar with the department’s research, brand, and goals and in regular contact with departmental leadership to ensure videos align with their vision. That said, success doesn’t depend upon having a dedicated communications position. These videos can be produced by any staffer with the needed skills, as long as those responsibilities and expectations are included in their job description, in order to ensure accountability. As administrators know, working these into a job description is not always straightforward. It will sometimes need to wait until an existing staffer leaves his or her position, at which point the department can work with human resources to recraft the description and adjust compensation assumptions accordingly. It can also be folded into a more general line in the job description, such as “Will produce multimedia assets that communicate the department’s research,” and the administrator can subsequently look for video skills within the applicant pool or gauge a candidate’s interest in the interview process.

The easier (not to say easy) approach is to identify an existing staff member who is interested in developing production skills and take advantage of professional development programs at your institution. At MIT, any employee can submit a professional development plan to human resources, which will reimburse the employee up to $5,250 per calendar year for courses taken elsewhere that develop skills related to their career goals.[7] I used this benefit to take a video production course at Harvard University’s Extension School.

As a rule, don’t hire students as the lead on producing research videos. But do identify students with talents that they could contribute to videos, especially illustration and photography—b-roll material that doesn’t require more than a few hours of work.

If you feel that students are your only option, tie deliverables to appropriate compensation, such as course credit, and scope the work to a student’s schedule.

Tips for rapid creation of video. Some of these tips are best practices for any video producer, but they are especially important for research videos that attempt to tell stories about complex topics.

Transcripts and captioning. For video that includes interviews or presentations, a timestamped, speaker-identified transcript is the best tool for a quick turnaround of a research video. Transcripts allow you to identify the most valuable parts of a video before editing begins. You can then piece together the footage into the story you want to tell. It also means collaborators can work quickly from a set of common materials, rather than try to view and annotate raw video together. Thus, since the desired topics are usually scattered in chunks throughout original video, transcripts let you reorder those parts into something coherent.

My transcription vendor has proved to be fast and affordable. Each bit of speech (roughly equivalent to a paragraph) can be timestamped down to the second it appears in the video, and depending on the information you provide, speakers can be identified by name or simply by a number (Speaker 1, Speaker 2, etc.).

This also means you can caption your videos. Reiterating a point from earlier, captioning is not legally required on videos purely telling stories about research but may be if the video has an instructional component. My recommendation is to pay for captioning if 1) your budget affords for what is only a modest additional cost and 2) you plan to upload the video to a site like YouTube that allows users to turn captions on or off. Just note that captioning should be done only after the final video is produced.

Pre-interviews. Whether done on-camera or off, pre-interviews are another best practice for videos that feature speakers talking about their work. Budget time for them—more, in fact, than for the production itself.

Pre-interviews serve several purposes:

- They establish a rapport between the subject and producer, putting the speaker at ease.

- The producer gets a chance to better understand what may be a complicated topic, even if they have done thorough preparation.

- The subject gets to rehearse and clarify descriptions of their work.

- Producers have the opportunity ask questions as if they were the intended audience, which functions as a reminder to the subject of the video’s purpose. “That’s a fascinating point about digitally annotating Moby-Dick. For anyone who hasn’t read it, what should they know about it and about what your work on digital annotation brings to it versus other books?”

For videos with interviews, restate and recap—and sometimes interrupt. Data scientists live by the phrase “garbage in, garbage out”. It’s the same with video. If you start off with bad material, your final product will be too. Aside from strong planning before the shoot, the best way to create good original material during the shoot itself is to remind the subject that they are allowed to be dissatisfied with their answer and can take another stab at it and to ask the subject to rephrase anything you didn’t find clear. At the end of a question or interview, you can also have them recapitulate their statements. This needn’t disrupt the flow of the conversation, by using open-ended[8] prompts such as:

- “How could I better understand your statement that…”, and do so with an old trick, purposely restating their words less than accurately so they are obliged to get at something clearer.

- “That’s a lot fascinating stuff to take in. What do you want [fellow faculty/prospective students/donors] to take away from this?”

- “I suppose that dovetails with [other research]…”

However, sometimes you do need to disrupt the flow. Interview subjects can stray too far from the topic.

During the shoot, make notes of good material. You will see or hear something you are certain you will want to review or use. It might be a funny story or illuminating statistic or just a lovely moment. If it was a statement, write a short exact phrase from it that you search for later in the transcript. If it was something visual, you have a few options. You might have an assistant who has marked the start time of the shot and, with a nod from you, can note the time you wish to come back to, or, if you are on your own and aren’t able to track the precise time, there are some unobtrusive workarounds, such as starting a recording app on your mobile device at the same time you start your video and tapping the body of the phone when there is a moment you wish to return to. You will be able to identify the sound when you view the waveform of the phone’s recording in your editing software, which will be roughly synced to the video and other audio.

Fit it into a communications plan. A video requires a big time commitment: it should serve a departmental strategy. If you are serious about videos as a way to communicate research, there should always be more than one in development, with an eye toward things like faculty book publication dates, departmental milestones (the appointment of a new head, for example), and school priorities (such as a capital campaign). There is a temptation, however, to produce a video simply because you are excited about a given piece of research. Excitement helps, but it’s not sufficient. Videos are too resource-intensive to be made outside of a communications plan. The only exception is if their purpose is to develop in-house video skills.

Budgeting

As a rule, concentrate your budget on hardware (tripods, etc.) and audio equipment, not necessarily the camera itself. If your department does not already have the following, acquire them. The dollar amounts suggest a lower bound for acceptable quality and an upper bound above which you may be paying for more than you need.

- A camera. $500 to no more than $2,000. Digital SLRs and even mobile phones can now record video of a quality more than sufficient for online viewing, but it takes some doing to capture acceptable audio, especially if there are multiple speakers. A mid-line professional video camera is preferable. If you go with a professional camera, it should have a flip-out screen for easy framing on the go. (A good place to get oriented is Shutterstock’s post “How To Choose The Best Camera For Your Video Production”

- A shotgun mic with wind-shield. $100 to no more than $200.

- At least two wireless mics. $150 to $300.

- A high-quality ball-head tripod. $125 to $150. Tripods are not an item to skimp on.

- Headphones. $40 to $70.

The low-end total would be about $900 and the high end about $2,700.

You will likely want a light kit as well ($150 to $300), but they are bulky, fragile, and tricky to set up quickly without one or more assistants. Not having one can restrict the possibility of shooting certain kinds of videos, especially two-camera interviews. Booms are another kind of equipment that, in any other video setup, would be a given, but they aren’t practical if a single staffer is managing everything.

I use the word acquire above rather than purchase because there are often campus-based sources of rentable equipment, staff or faculty who are willing to lend equipment on a one-off basis, or related departments that are willing to share resources. This is something to take advantage of if you want to do a video production trial run of before budgeting for equipment or staffing.

Be sure to budget for transcripts and captions. ~$3-4 per minute of footage.

To track the opportunity cost of a staffer not working on something else of value, budget for a percentage of their compensation. The low end is at least $2,000 annually, though expect between $5,000 and $10,000 based on the value of the work they are forgoing.

Finally, budget for professional education if your institution does not offer a program funded centrally. Of varying quality, video production courses can run from less than $1,000 at community colleges to more than $5,000 at university external education programs. You might prefer to research other options, instead. There are community media centers that offer low-cost instruction in return for permission to air your content, and HR offices will sometimes assist in finding outside instructors for seminars if enough other departments express interest.

When to pass on the whole idea of producing research videos…or, when to cut your losses.

Let’s make explicit the signs that augur against starting—or continuing—a research video production initiative within your department.

A department should pass on making research videos altogether if it lacks:

- A staff member who is directly accountable for the production.

- Multiple research projects that lend themselves to video, to shoot first while capacity/experience is built up to handle more creative videos later.

- Distribution channels. This doesn’t just mean your own channels (website, social media accounts, email lists) but participation from those outside your department. Hesitate if your school/communications office doesn’t help share research videos, for example. Or consider your editorial options if your audience uses one tool but not another: faculty may want it on YouTube so they can link to a specific time, while prospective students may want short clips distributed on Snapchat. If you don’t have established distribution channels or don’t know who uses yours, your videos may reach too few people to make the work worth it.

A department should abandon a current production if it has:

- Inaudible audio/unintelligible speech.

- Footage that is consistently poorly framed.

- A focus that strays far from the department’s communications goals and a prompt reshoot was not possible. With post-production being so time-intensive, it is not worth completing a video that will immediately have no strategic use.

- Usage rights unsecured for all essential material.

- Material subsequently contradicted by events or new research. If events or research add to the material, that can be acknowledged in the video. But you never want to distribute a video that included a prediction later proved false.

This brings me to a final point, one that always worries my communications colleagues and is my one criticism of Stein’s paper: proof of success is hard to come by. Stein argues her video recruited freshmen, contributed to the finalization of an international student exchange program, generated internships after its screening for a dean’s panel, and “garnered a note of praise” from a new chancellor (298-299). “[T]he completed video,” she says, “met with considerable success, fulfilling most of the goals for its undertaking.” However, she does not draw the line between a video’s content and style and its purported outcomes, except perhaps its pedagogical value. Her evidence indicates only that it was better to have made the videos than to have not. She is correct, but it does not help us measure whether it was better to have made a video than to have done something else. Today, we in higher education departments can measure effects of communications and outreach a bit better than a decade and a half ago. When it comes to recruitment, for example, we can now survey applicants for free after the application deadline to ask “Did you view our department’s videos? If yes, did they make you more likely, as likely, or less likely to apply?” Departments would then have to decide how many “more likelies” justify the time and expense of producing a video (Stein’s took nine months to produce (299)), versus putting those resources to other recruitment uses. Stein’s department could only rely on a collective gut feeling. This reality has not changed much since 2000. The sample size of applicants, potential donors, peer faculty, and other departmental research video viewers isn’t large enough to make the same kind of statistical inference of value that, say, an online retailer can make when they track a user clicking a video teaser of a product on Facebook, then viewing the full video on its product page, then adding the product to their online cart and purchasing it.

Developing a method to capture these metrics for a small- to medium-sized academic department would be a clear next step in this research.

That said, Stein rightly hammers home the value to a department of the exercise of producing a video (300). Hers surfaced the mixed ways faculty defined their own department, that it “had helped uncover previously undetected commonalities that have existed among different factions,” that it helped begin “investigations into potential projects with colleagues across concentrations,” that it was a “revelation of greater unity” that “performed a bridging function in revealing unrealized intersections of interest and research”. This is, in fact, a strong argument against my recommendation that videos focus on single bits of research instead of something that tries to represent an entire department.

Conclusions

This paper offers lessons about producing video about research in academic fields that do not typically lend themselves to visuals. Across all three case studies, we learned that, first, video cannot work without good audio and you should therefore concentrate your budget and training on audio production. Next, start with the researcher in mind, rather than coming to them after filming students, events, or other more-difficult-to-film subjects. Third, take advantage of visuals like graphics, slides, third-party video, and student- or staff-made illustrations and animation: you know what you will get if you use existing resources, and with appropriate supervision, you can get what you need from custom illustrations and animation. Fourth, be a little obtrusive when it comes to getting the material you need from an interview subject. Fifth, edit with a transcript. And, finally, don’t be afraid to abandon a project that no longer meets your needs.

All that said, only three case studies inform these lessons and they represent just three approaches, which were informed by what our survey shows is still a research storytelling method that departments have not experimented much with. There would be different takeaways for videos that feature fieldwork, or ones featuring a research collaboration across multiple universities, or projects where the departmental producer is playing a supporting role to a school communications office’s full-time videographer. Our survey and conversations, all the same, show there is an unmet demand for department-made videos. We hope this paper, three case studies, and list of lessons function as a rough guide for administrators to move toward their own video production goals.

References

Fair use. (2016, March 13). In Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Fair_use

Gayla, M. A. (2016, February 25). Judge Recommends that Disability Lawsuit Proceed. Retrieved March 21, 2016, from http://www.thecrimson.com/article/2016/2/25/harvard-lawsuit-deaf-proceed/

Jenkins, H. (2009, February 11). If It Doesn’t Spread, It’s Dead (Part One): Media Viruses and Memes. Retrieved from http://henryjenkins.org/2009/02/if_it_doesnt_spread_its_dead_p.html

Lee, M. J. (2014). Creating Conservatism: Postwar Words that Made an American Movement. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT. (2014). Genome Editing with CRISPR-Cas9. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2pp17E4E-O8

Syracuse University, S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications (2012). Public Diplomacy: What Is It?. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r_l121KXGPw

Stein, S. (2000). Multimedia as Persuasive Agent: Using Visual Metaphors To Establish the Rhetorical Agenda in a Communication Department Video. JACA: Journal of the Association for Communication Administration, 29(3), 293–303.

Whitacre, A., & Wood, H. (2014a, November 5). Video Use in Humanities Programs (Responses). Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1ZDDkIz714Y-CyfTUOI5geZBBslPEzwXSjKMycsZz_NY/edit#gid=792729952

Whitacre, A., & Wood, H. (2014b, December 10). Follow-Up Video Survey (Responses). Retrieved March 21, 2016, from https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1LSorUUde54eXKBWkHv_4zFznF-bVveptOdQQEPxyi-U/edit

Worcester Polytechnic Institute. (2014). Explore Music Technology at WPI. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ZmDb47cE8c

Notes

- Or then there is NCA award-winning research you absolutely don’t want visuals for: “Comparing tailored and narrative worksite interventions at increasing colonoscopy adherence in adults 50-75”. ↑

- And where she documented the departmental politics involved in deciding what to include, well…some things don’t change. ↑

- I should re-emphasize this distinction. I am looking at academic departments–not schools or central administration offices like news offices, student life, etc., which also produce video. ↑

- This is easy to do for a given production, but if your school repurposes departmental videos for online education, you will want to know ahead of time who is required to pay for closed captioning. ↑

- Data Storytelling Studio course description: “Explores visualization methodologies to conceive and represent systems and data, e.g., financial, media, economic, political, etc. Covers basic methods for research, cleaning, and analysis of datasets. Introduces creative methods of data presentation and storytelling. Considers the emotional, aesthetic, ethical, and practical effects of different presentation methods as well as how to develop metrics for assessing impact. Work centers on readings, visualization exercises, and a final project. Students taking graduate version complete additional assignments.” ↑

- Example of poor audio. Unsteady reframing due to an old ball-head tripod and a moving speaker meant the shotgun mic was not always pointed at its target. ↑

- Not necessarily related to their current position. At MIT, the standard for professional development reimbursement is that the course must prepare the employee for professional advancement in their current field or a different field “in which realistic full-time employment opportunities exist at” the institution. ↑

- Open-ended prompts solicit the most material. But interviewers, especially if their questions will be heard in the video, should use yes-or-no questions as well in order to have shorter, more declarative statements to work with later. These function to give viewers a breather between longer answers and offer the option of a clear end to a segment. ↑