Navigating between the humanities and sciences is an art of good communication. What unites these academic disciplines, colored by the artifice of its own creation, is the human classifying history, politics, and literature in one folder, and biology, mathematics, and physics in another, before one morning, squinting her eyes, struck by the ambiguity of the philosophy of science or the neurobiology of linguistics, she realizes that her arm that writes has arteries pumping white blood cells while the words she’s reading aren’t any less literary despite spelling “ventricular fibrillation.” This idea of interdisciplinarity that’s so well-learned from a liberal arts education, for whatever reason, becomes diluted into the everyday customs of the professional world, with its industry values and ways of being that impact so many people. What keeps the core of humanistic values in this landscape, however, is storytelling, the sharing of experiences between people.

How can this practice be reimagined and adapted to keep pace with the current age while maintaining both the integrity and social relevance necessary to create measurable impact?

What drew me to my internship with the Open Documentary Lab last year is precisely this question. Over the summer, I organized the Docubase, a curated catalogue of documentaries using innovative practices, based on the techniques and technologies used by each project. A task that seems straightforward at face value actually profoundly influenced the way I thought, inspiring a greater creativity for imagining the range shapes and forms that media could take to tell stories in the digital age. This experience influenced by approach with the Calla campaign, a media initiative inspired by a new medical device developed at Duke University, which enables self-screenings of cervical cancer without a speculum or gynecologist, increasing the comfort and access to reproductive healthcare. A core part of this healthcare initiative is to amplify narratives that destigmatize the cervix and reproductive anatomy and strengthen networks that promote positive health outcomes.

I was fascinated with the Callascope as not only as a medical tool, but also as a media object itself. How can the image of the cervix be used not only for a medical diagnosis, but also as the enactment of a new truth, much like film photography did in modern history? And to go even further, a feminist truth, one generated by a woman or nonbinary person as an active agent in the process of self-inserting the device and capturing an image of their own body. The Callascope embodies how media goes beyond representation but is deeply embedded in the realities we live, in this case, our health outcomes, which are impacted by the information that comes with such image-producing technologies themselves.

For the past few months, as a post-baccalaureate fellow and documentarian, I had immersed myself into the Callascope’s story. I heard the tale told from its beginnings, in its prototyping phase in a research lab led by Dr. Nimmi Ramanujam, director of the Center for Global Women’s Health Technologies, and Mercy Asiedu, now a Schmitt Science Fellow joining MIT CSAIL this fall. And I followed the story in its present, when I joined Mercy in Accra, Ghana as she conducted early clinical studies of the Callascope, and we worked together with photographer Fati Abubakar to see how such medical innovations fit within the fabric of community health systems. Now, I’m co-creating the story’s future

by integrating the healthcare, education, and media initiatives of this project into a digital storytelling platform and community that invites crowdsourced participation.

The path to interconnect these three facets, however, has been a journey of gradual discovery. In 2018, to improve the design of the device, the lab conducted research studies in which women would take the Callascope home to identify their own cervixes, then audio record their reflections after their experiences. The findings were profound— an engineering lab had inadvertently collected oral histories. Upon realizing the expressive potential of the Callascope, GWHT started collaborating with the Center for Documentary Studies and Health Humanities Lab to bring artistic approaches to their shared interest in storytelling. The Callascope’s development prompted the idea that barriers to reproductive healthcare and cervical cancer screening are not limited to the economic and structural components in regard to access alone. More women also need to become active agents in taking care of and advocating for their bodies, which requires a cultural shift in mindset that destigmatizes female reproductive anatomy.

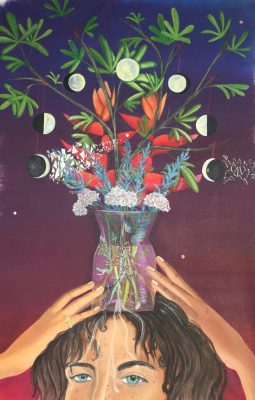

From this point the Calla campaign emerged. We would share the transcripts of the initial at-home studies with artists, then prompt them to reflect on their relationship to their bodies and cultures. This led to an experimentation of projects of different mediums and audiences, including an art exhibit, educational workshops, a documentary, a video series, all inspired by the synergetic connections that artists would make between their work and the research itself. Now, students are continuing to conduct more studies in various communities globally, gathering culturally-specific data about reproductive health perceptions. With this model, we’re continuing to engage more artists and build a global community around this work.

Working on Docubase last year introduced me to ideas about transmedia projects that would guide me, but it was only through working concretely with the Calla campaign that I truly learned of the challenges of communicating between researchers and artists, battling my own preconceptions about these borders. The innovation required for this task alone changed my notion of what it means to be a “documentarian,” and I’ve found that co-creating social narratives is not work that is limited to the confines of any one medium or discipline alone. With the Calla campaign, I immersed myself into the engineering and reproductive health field but zooming out from my own experience allows me to imagine similar challenges for so many other global issues. Entering CMS/W as a graduate student will be an introduction a new normal, in the midst of a diversity of projects vast to a humbling degree. I can only but wear a suit of maximum absorbency – the Boston waters are indeed cold, I hear, but in preparation, I await!